Evaluating the Motivational Dimensions of the STEM Learning Experiences with a Robot#

In 2018, as the learning experience designer and engineer at DJI, I led the launch of RoboMaster S1(RMS1), a STEM educational robot. We conducted many rounds of surveys, interviews, focus groups, and tests to help design and validate the learning experiences. We continued to iterate and develop new content after the launch. However, at 2022, when I was at Harvard Graduate School of Education, taking a course by Prof. Chris Dede, I learned a lot about Motivation and Learning. I wrote down this evaluation piece to revisit and reflect the existing learning experiences of RMS1 so that my colleagues at DJI could further improve this innovative product.

Introduction#

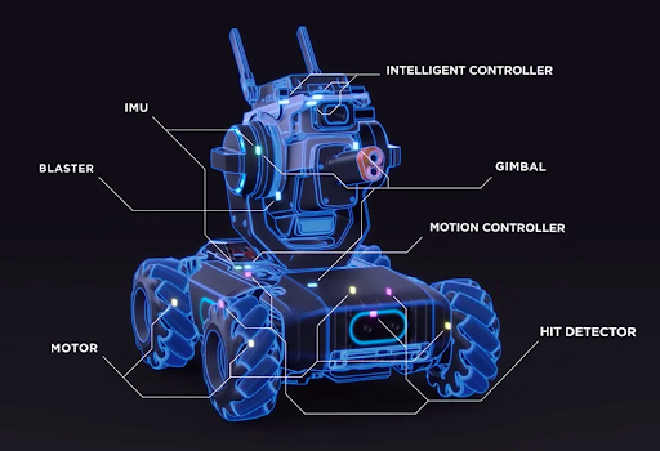

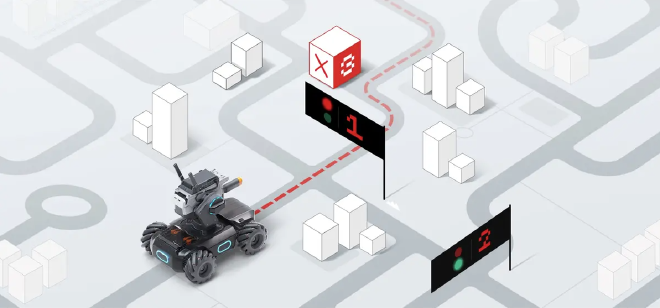

The pace of innovation is accelerating globally and with it the competition for scientific and technical talent. It has increased attention to effective and inclusive STEM teaching and learning. Researchers and educators have proposed various approaches for engaging students more. One of these approaches is to use robots in introductory programming learning which includes building or using an interactive physical system with a combination of software and hardware (McGill, 2012). In fact, physical computing with robots is a proven concept to attract students to STEM learning and to increase their motivation to learn programming and related computational skills(Janke, E., Brune, P., & Studt, R,2013). Not only in classrooms, it has also been demonstrated that using robots as tools can improve students’ content knowledge in STEM fields and critical thinking skills in an informal learning environment (Barker & Ansorge, 2007, p. 231). RoboMaster S1 (RMS1) is an intelligent educational robot inspired by DJI’s annual RoboMaster robotics competition. According to the website, RMS1 aims to let users dive into the world of robotics, programming, AI, math and physics through exciting intelligent features and captivating gameplay(“RoboMaster S1 - DJI”, 2022). An app that controls the robot supports omnidirectional movement gel bead launching and provides an immersive first-person view driving experience.

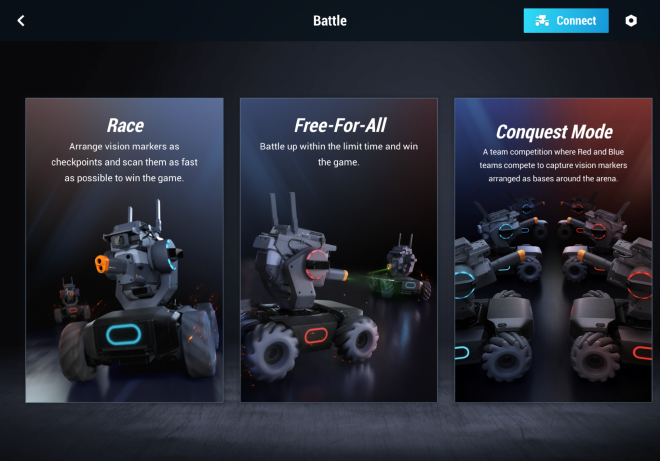

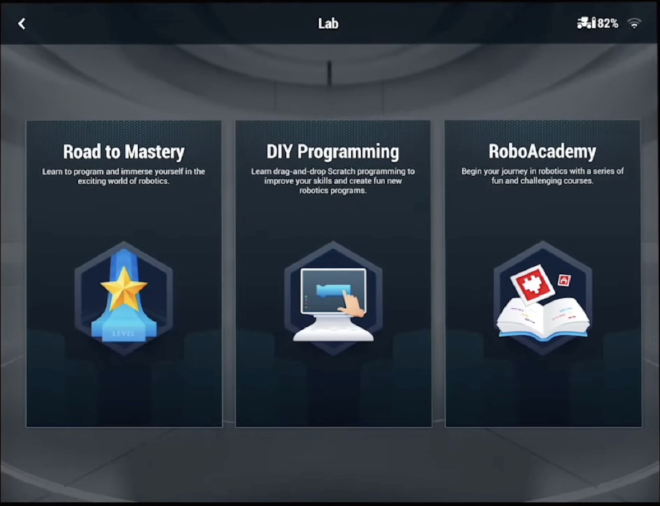

In this post, I analyze the learning experiences in the RoboMaster app, including three main sections: “Solo”, learning through free control of the robot, “Battle”, learning through competition with others, and “Lab”, learning STEM knowledge through tutorials. The motivational dimensions of these experiences encourage players to develop their robot controlling skills, strive for mastery in the “Battle” mode, and continually expand their STEM knowledge. These findings will be shared with the RoboMaster development team to assist them in creating more engaging learning experiences for users of various personalities.

Learning Experiences in RoboMaster#

Solo Mode#

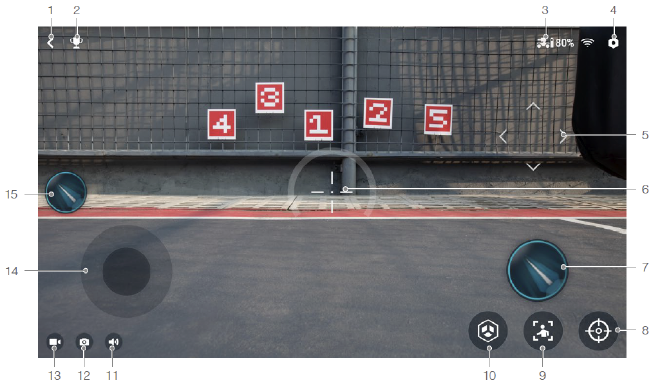

Usually, users start exploring the RMS1 from solo mode. This process allows the user to quickly learn about the robot’s components and functions. When controlling RMS1, the app defaults to a first-person view of the action, letting users steer the robot just like they were inside it—similar to playing a first-person video game. Users can also fire the tiny gel beads with a tap or switch to an ultra red “laser” shott (a little flash of colored light with a pew-pew sound). Moreover, the camera allows users to film videos and take snapshots. Thanks to computer vision technology, users can even identify a person within the frame and have the RMS1 follow them around.

Battle Mode#

The Lab#

The educational problems#

RMS1 was designed for users to learn with a tangible robot, bridge the digital world with the physical one, and bring abstract theories to life through practical operations. The learning experiences aim to help youth understand STEM concepts, and most importantly, motivate them to learn. Motivation is a critical condition for productive learning (Pintrich & Schunk, 2002) and it also affects the acquisition and demonstration of higher-order thinking skills (Wolpert, 2008). Therefore, this study aims to find out whether the learning experiences with RMS1 are effective in creating motivation to learn STEM. Additionally, this study asked how RMS1 users experience their informal learning environment to understand whether and in what ways they find themselves engaging. Compare the findings to claims made by advocates of learning with Robots. In the next section, I will first introduce the theories of motivation from the learning experiences in the app. Then I will connect them with the design elements from each experience. In the feedback and interview section, discuss the comments and feedback from the user, data collected from the survey, and the interview findings. In the overall assessment section, present an overall comparison between the strengths and limits of the motivational aspects in the three main experiences. Finally, a discussion concludes the study with a discussion of future opportunities and challenges.

Theoretical Framework for Analyzing this Experience#

In order to analyze the learning experience of this app, let’s first assume a learning situation. Thus the learning activities happen in an informal learning setting. According to the website’s guideline age of use, in this study, I assume the user’s age range to 14 years old and above, with no prior experience with programming in Scratch. Based on this setting, I came to identify the features that motivate users in the learning process. I would like to evaluate the features that motivate learners through the perspective of the Self-Determination Theory. Lastly, to encourage learners to continue exploring STEM concepts, I would like to review the existing tutorials according to the theory of ZPD.

Self-Determination#

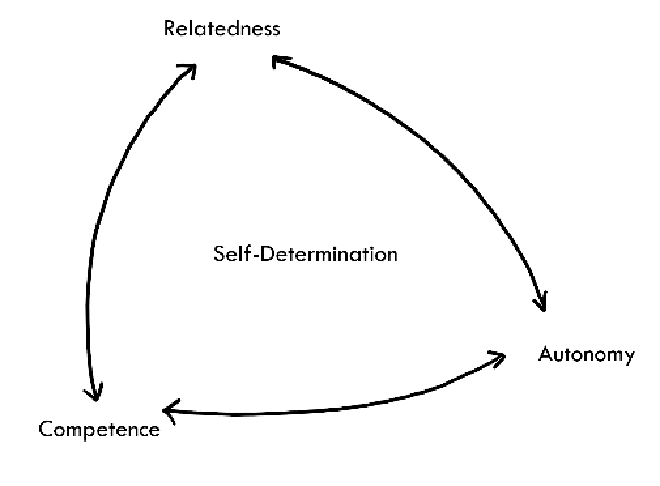

As online entertainment, social networks, and digital gaming in all kinds of platforms provide competing interests for teenagers’ attention, how to motivate the academically unmotivated becomes increasingly pressing. Players often spend extended time playing games to gain mastery over the challenges posed and to progress to higher levels of the game. The idea of Robomaster was actually inspired by robot animation and some video games. RMS1 kept the same game gene but aimed to apply players’ desire for progress to motivate STEM learning intrinsically. To investigate the impact of increasing intrinsic motivation, the theoretical basis of this study is the Self-determination theory (SDT). The underlying belief of this theory is that individuals’ intrinsic motivation can be triggered by three basic psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness(Ryan and Deci, 2000).

Competence - “I want to be able to do a good job.”#

The feeling of competence is a sense that one is effective at doing something. It is really commonly studied in psychology as a core psychological need. Essentially, the learning environments and settings can have a big impact on the level of competence.

Solo mode: Solo mode introduces users to quickly master how to control the robot’s movements and follow the prompts to try out the robot’s various functions. Once the user has mastered the basic operations, they can engage in two practices designed to continually enhance their competence as they progress in controlling the robot: ‘Target Practice’ and ‘Target Race’." These mini-game-like experiences can help users achieve high levels of competence in various skills and abilities, such as problem-solving, and reaction time.

Battle mode: This mode offers three mini-competitions that allow users to compete against others. The difficulty levels of these competitions are designed to provide a progressive experience, enabling users to continually enhance their competence as they advance in controlling the robot and programming. As shown in image, the “Conquest Mode” employs a simplified version of the competition system used in the RoboMaster University Championship, which is a Player versus Player (PvP) live-firing robotics competition. Purposeful and goal-directed competitions can motivate users to be more tenacious and persevere through challenges. Competitions serve as an engaging approach to hands-on learning, raising students’ interest in acquiring related conceptual knowledge and skills. Robotics competitions have gained increasing popularity within the technology and engineering educational community. As Caron (2010) states, “Competitions add a level of engagement that is often hard to achieve in a traditional classroom setting” (p. 21).

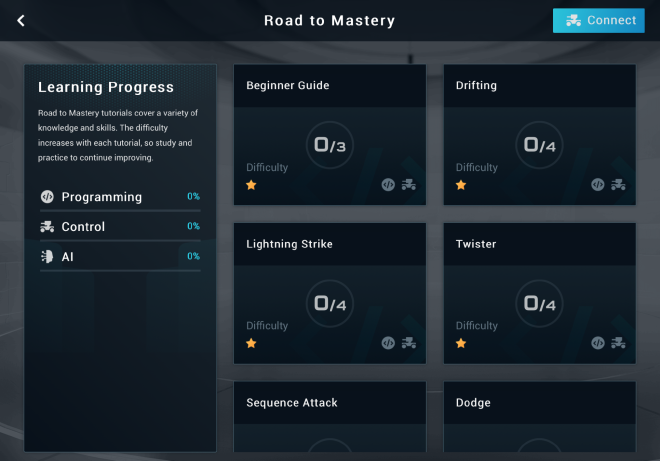

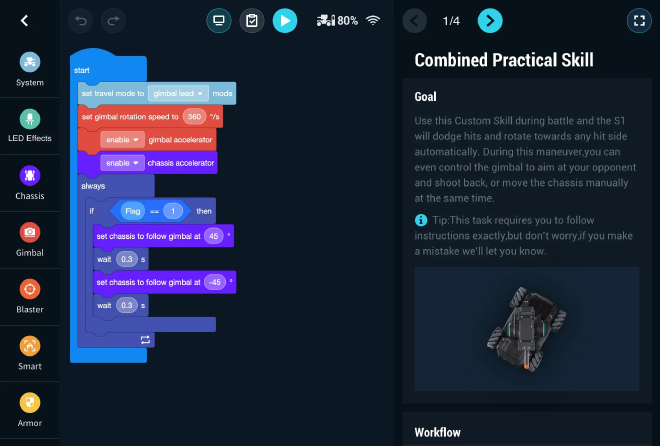

Lab: During gameplay in the Solo mode and Battle mode, users may encounter prompts instructing them to utilize “Skills” during operation. Users can acquire new skills for the robot either through the ‘DIY programming’ option in the Lab or by completing the ‘Road to Mastery’ tutorials. The ‘Road to Mastery’ comprises eleven Blockly programming tutorials, starting with the “Beginner Guide” and progressively increasing in difficulty. Users can learn to control the robot, starting with simple tasks like spinning and culminating in identifying and attacking specific targets. The lessons become increasingly complex, covering dozens of different tiles that determine the robot’s movement. Striking a balance between difficulty and user skill was crucial for the success of these tutorials. Upon completing a tutorial, users receive star ratings, indicating their effectiveness in achieving the programming goals. These features provide performance feedback and acknowledge the players’ prowess, which are key to satisfying their need for competence, as discussed by Ryan and Deci (2000a).

Autonomy - “I want to choose the things I do.”#

Autonomy is the ability of an individual to be initiators of their own actions and assume psychological freedom when engaging in experiences. It can be supported through choice, acknowledgment of feelings, and opportunities for self-direction. The RMS1 app enables users to have in-game choices over goals and strategies and experience varied opportunities for action in the solo mode, to advance through challenges and levels in the tutorial. Achieving a greater feeling of like one has control over things they do enriches users’ intrinsic motivation.

Solo mode: Various choices and control options are available here. Default, the solo mode will lead users to the FPV screen, so they can see what the robot sees and they can move the robot around by dragging the virtual joysticks. Users can remotely control many components of the robot, such as controlling the chassis’ omnidirectional movement, controlling the gimbal’s movement in three axial directions, and trying to use the function of recognizing visual markers, recognizing pedestrians, and recognizing hand gestures. In this process, users will implicitly experience some STEM concepts or phenomena, such as how the distance between the marker and the camera changes the robot’s perspective. After knowing the basic operation of controlling the robot, the solo mode allows players to advance through different two-game challenges or to explore the physical world freely. The choices to continuously balance their boundless curiosity against a finite pool of resources. For further challenge and learning, there is a function that leads players to move on to the Lab. This Custom skills button from image: User can equip their own code as a function during race or combat with others. The enjoyment, and satisfaction from the solo and battle mode lit up the intrinsic motivation to make users want to level up their robot.

Lab:

When the user leaves solo mode and goes to learn through tutorials in the lab, they are actually showing a desire for progression to develop more skills in the robot. They have three formats of learning to choose from in the Lab:

- “Road to Mastery”: Learn by following project-based tutorials.

- “DIY Programming” is a programming playground. If anyone wants to go deeper into coding, the RMS1 also supports Python here.

- “RoboAcademy”: access to video courses, programming guide, and developer documentation.

Free selection of a task indicates users’ motivation to perform the task (Pintrich & Schunk, 2002). When a user chooses to become a learner in “Road to Mastery,” one can select tutorials based on difficulty and knowledge. In Figure 2-4, the icons at the lower right corner of each tutorial indicate the direction of expertise for that tutorial. For example, in the Beginner Guide, the two icons point to “programming” and “control.” Each tutorial has demo videos that introduce learners to the covered knowledge and skills. Ideally, by providing three different learning modes (Road to Mastery, DIY Programming, RoboAcademy), learners have the freedom to choose when and where they want to learn. The Lab strives to generate almost limitless learning activities and thus support the choice of each learner, which further increases their sense of autonomy and enhances learners’ motivation.

Relatedness - “I want to be closer to other people.”#

Relatedness is feeling cared for and connected meaningfully to others. It has to do with a sense of belonging, a feeling that you matter to the other people there. Relatedness is enhanced not just by people treating you warmly and including you, but your giving also enhances it to them, and you are able to matter in their lives. That’s part of what helps us feel connected. So, it’s not a one-way street to relatedness. It has to do with both. Compared to learning about STEM with a computer or a book, learning with a robot can leave a strong impression on users. Their tangible user interface and body attract users’ attention(Kanda, 2004). A study about the impact of using an educational robot even predicted that robots are highly likely to become successful social actors in mixed-reality environments(Chin, Hong & Chen, 2014).

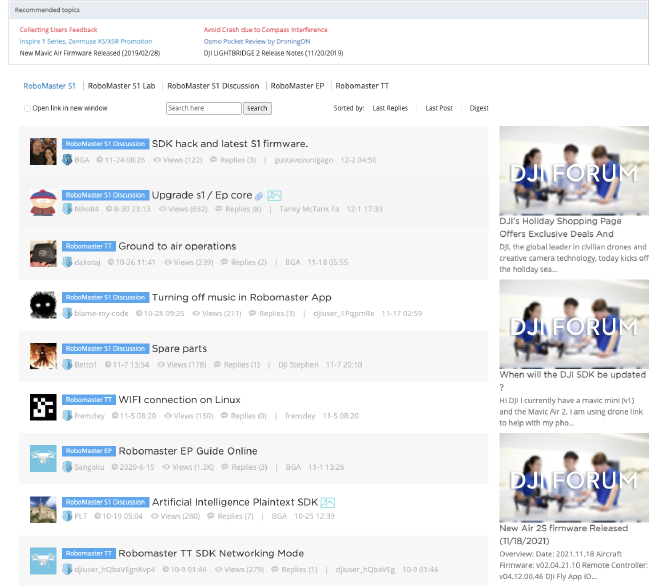

Community of Practices#

After all, the innate need for relatedness is more about belongingness and connectedness with others. The learning experience with RM introduces users to a club of robotics lovers, where people have various forms of playing and learning together. Participating in the club is an informal, continuous, and naturally occurring learning process, Lave and Wenger (1991) used the term “community of practice” to describe such a place where interactions happen between novices and experts and the process by which newcomers create a professional identity. The user base of RM is from different levels of participation. Like professional programmers, engineers, and down to young children who just started to learn scratch. There is a knowledge-sharing forum for RM lovers and many WeChat groups, where participants come to learn from one another with a focus on problem-solving and innovation. These communities of practice gather to discuss topics related to a specific task or role that each member has in common. It creates an environment of shared experience that enables participants to compare methods and processes – benefiting all. This also establishes a “safe space” that enables users and learners to develop social bonds, allowing them to cooperate with geographically remote peers (Przybylski, Rigby & Ryan, 2010). Physically, there are local RM clubs in major cities in China, where users can find and give support, meet, and participate the in-person events.

The satisfaction of all these three psychological needs by the features of learning with RM leads to a greater level of motivation. Frequently, the interrelation within them can promote a higher level of self-determination within individuals.

ZPD and scaffolding#

In the previous sections, I only assumed the age of users but did not set an entry threshold for STEM knowledge. It is essential for such an app designed for users to provide enough scaffolding to support users from different knowledge bases and encourage them to explore and learn actively. To do so, first, however, it is difficult for the app designer to know the level of development of the user to complete the task independently without help. Secondly, it is also challenging to see the level of the user’s capability when working with capable others. The distance between those two unknowns is what Vygotsky called the “zone of proximal development”(1978).

RMS1 app’s predefined user scenario could be all users learn from scratch. Thus at the beginning, the learning opportunity matches the learner’s prior knowledge and experiences. However, the pace of learning development could be very different, which requires different motivational schemas that enable them to understand the domain’s value and experience its satisfactions (Brophy, 1999). In an informal learning environment, the app itself does not examine the user’s existing knowledge at all. However, as far as I know, this product is also used in formal teaching as a STEM explory course in schools and tutoring organizations. I believe that the teacher’s guidance can significantly enhance learners’ development.

Solo mode:

I didn’t find many features that work as scaffolding in the solo section. For people who are used to remotely controlling robots or racing cars with joysticks, it looks like they don’t need any learning to operate RMS1. However, they probably have never controlled the gimbal movement, the movement of individual wheels. The UI of this section would be better if it showed direct visual cues to help users better adapt to the robot’s essential remote control. Then introduce the different components of the robot. It is also important to design the timing of the appearance of these direct instructions. Once users have mastered the operation of a particular part of the robot, introducing a new component can further encourage them to learn.

Lab:

The tutorials in the Lab cover different levels of difficulty. The content knowledge includes core programming skills of robot control and AI, supporting game performance. Each of the tutorials is divided into several chapters. When users complete a chapter, they receive feedback on whether they have programmed it correctly. In addition, the app automatically saves all the content they programmed in the tutorial, so users don’t need to start from scratch when they log out. Furthermore, on the home page of the tutorial, users can see their progress for each tutorial. As the user passes through tutorials, they begin to master different categories of programming blocks. For example, the first tutorial simply teaches how to program the robot chassis. This particular tutorial has a refined version that controls each of the four wheels to present the same effect of preventing the robot chassis. Such design features allow users to continue having feelings of competence through the challenges available to players. Also, it enables feelings of autonomy through possibilities to create complex control for the robot. Towards the increasing need for programming, except for the in-app tutorials, there are many user-generated tutorials in the forum, provided by ‘more knowledgeable others.’ There is also a thread of Q&A, which offers more assistance when users get stuck in the tutorial.

Gamification#

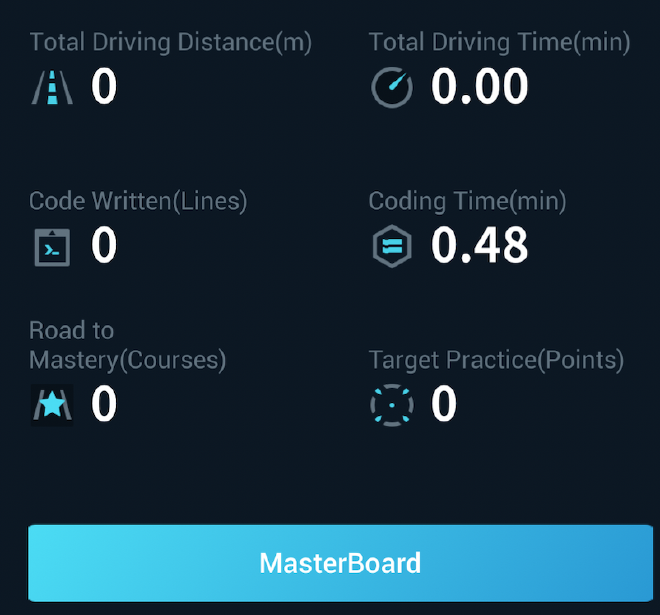

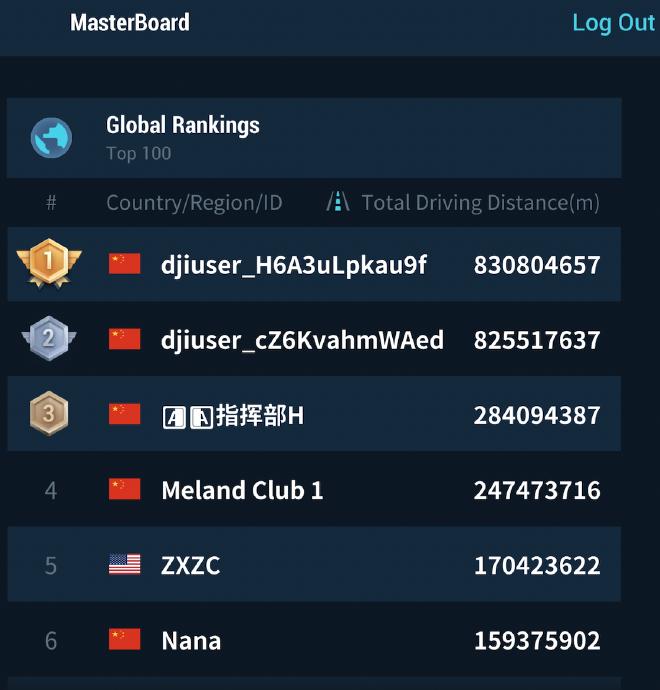

Gamified elements can be found almost everywhere in the RMS1 app. Like many massive online games, the app even has a MasterBoard that shows the user’s personal data and global rankings. These gamified experiences can intrinsically and extrinsically motivate users to reach more goals. For example, practice controlling the robot to travel longer distances, write more lines of code, complete more tutorials, etc.

The automatic driving challenge from Battle mode asks users to utilize vision markers to create “traffic lights” and other obstacles. Users can write their own programs that allow the S1 to drive automatically and execute complex tasks. Explore mathematical principles involving robotic control and motion mechanics through the S1’s programmable artificial intelligence modules. Get an in-depth understanding of AI as you develop these skills and many more. Such learning experience covers knowledge, principles, information, and skills that need to be mastered.

In a formal setting, schools would choose to focus on the learning and have teachers teach students directly. But with RMS1, that content can be gained by learners from the game design. Modern learning theory suggests the situated learning approach is the better one(Shaffer, 2008). Learning with robots and with those gamified elements makes the uptake of knowledge and skills much more subtle than learning about STEM in the classroom.

My Personal Experience with RMS1#

I was involved in the development of the app and the robot. Before this experience, I only had knowledge of computer science, programming, and AI, and very little understanding of robotics. Through the tutorials in the app and the video tutorials from RoboAcademy, I learned a lot more about robotics and mechanical engineering. Before the pandemic, I used to see many teen users quickly get attracted to RoboMaster and started spending a lot of time on the app. On the other hand, I have also seen many users lose interest soon after purchase. Since I’m an RMS1 user myself, I entered the RM weChat group and got in touch with a few users who were willing to talk with me about their experiences with RMS1.

I approached 8 RMS1 users aged 15-36. They have all used RMS1 for more than six months. Since the user groups I reached were all from China, the interviews were originally communicated in Mandarin. I prepared an outline of the interview and translated it into Chinese to have a conversation with the interviewees. I recorded the conversation and translated important information to present in this study.

Findings#

- General: All eight of them have tried three main functions, but two users were not able to find local players to experience the battle mode. Among them, the most popular function is the Lab. More specifically, the DIY programming. All of them have tried Road to Mastery but none of them completed all the tutorials.

- Competence: All of them agreed that they felt having fun while using the RM. Only one interviewee was not sure about his programming made the robot stronger. He believes that it is his control that improves the robot.

- Autonomy: All of them thought that their are in control of the learning process. Most of them don’t have a preference for choosing tutorials, they follow the original tutorial order. 5 of them watched the video courses and found the contents helpful.

- Relatedness: All of them expressed that they found it easy to access the forum, and they found the link to the weChat group from the forum. They agreed on all the questions in the Relatedness section.

Overall Assessment of the Experience#

Strengths and limits in terms of motivation and learning#

The RoboMaster S1 app demonstrates significant strengths in cultivating intrinsic motivation among its users, particularly through its adherence to the principles outlined in Self-Determination Theory. By providing experiences that foster a sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness, the app succeeds in engaging learners and sustaining their interest in STEM topics and robotics. The competence dimension is well-supported through features like progressive tutorial difficulties, performance feedback mechanisms, and opportunities to showcase mastery in coding challenges and battle scenarios. Users interviewed expressed feeling a genuine sense of fun and enjoyment from operating the robot, indicating that the experiences effectively tap into their inner motivational resources. Autonomy is nurtured by offering choices in learning pathways, customizable programming options, and flexibility in exploration within the virtual and physical environments. The ability to personalize aspects of their robot enhances feelings of control and self-direction in the learning process. Perhaps most notably, the app cultivates a sense of relatedness by connecting users to a vibrant community of robotics enthusiasts. Through forums, local clubs, and sharing capabilities, learners can seek support, collaborate with peers, and feel a sense of belonging to a collective endeavor. This social dimension is critical for sustaining long-term engagement. However, the app does have some limitations, particularly in providing adaptive scaffolding tailored to individual learners’ zones of proximal development. Without mechanisms to assess existing knowledge and skills, the app cannot dynamically adjust the level of support and instructional content to optimally challenge each user. This one-size-fits-all approach may lead to frustration for some and a lack of depth for others. Furthermore, the dual objectives of the app - facilitating both robot control and STEM concept learning - could potentially create conflicting design priorities. Trying to serve these distinct purposes within a single interface may dilute the effectiveness of each experience.

Suggestions#

To enhance the learning experience, a key suggestion would be to decouple the control/gameplay aspects from the explicit educational components. This could allow for deeper focus and optimization of each domain. The control and battle interfaces could retain their gamified, engaging nature while integrating more seamlessly with insights from gaming psychology and human-robot interaction principles. Introducing narrative elements, progressive difficulty curves, and dynamic feedback loops could further elevate the immersion and motivation to master robot operation. Conversely, the learning environment would benefit from techniques inspired by adaptive educational technologies and intelligent tutoring systems. Implementing mechanisms to regularly assess user understanding through interactive exercises or knowledge probes would provide valuable data to personalize subsequent content presentation. An ideal adaptive learning system could use this data to determine the most appropriate next concepts, examples, or practice problems for each individual based on their demonstrated proficiencies and knowledge gaps. The level of scaffolding and guidance could dynamically adjust, gradually transferring more responsibility to the learner as their competence in a given area grows. Integrating multi-modal instruction beyond just text and visuals, such as interactive simulations, animated pedagogical agents, or even direct guidance from human experts, could further enrich the breadth of learning experiences available. Additionally, incorporating principles from constructionist learning theory could empower users to build and create personally meaningful artifacts that aid their understanding of complex concepts. The robot itself provides a tangible medium for this constructionist approach. From a practical standpoint, closer integration with formal educational contexts like classrooms would allow the app to complement and extend school-based learning activities. Teachers could monitor student progress, identify struggling areas, and seamlessly incorporate RoboMaster into their curriculum using learning management system integrations.

Bias and Limitations#

It’s important to acknowledge the inherent biases and limitations present in this assessment. As a previous developer involved with RoboMaster S1, there is an inherent affinity and natural inclination to perceive the product’s strengths favorably while potentially overlooking or rationalizing its shortcomings. This “innovator’s bias” is a well-documented phenomenon and should be accounted for. Moreover, the insights gathered from user interviews may not fully represent the general population’s experiences. The individuals interviewed were already active community members invested in the product’s ecosytem. Their perspectives could be skewed toward the more motivated and engaged end of the user spectrum. To gain a more comprehensive understanding, additional research involving a broader, more representative sample of users across various demographic groups, skill levels, and engagement levels would be beneficial. This could uncover further motivational barriers, usability hurdles, or untapped opportunities that this initial assessment may have missed. Furthermore, while the theories and principles applied here, such as Self-Determination Theory and Zones of Proximal Development, are well-established, their specific applications and interactions within the context of a robot-based STEM learning environment have not been exhaustively validated empirically. More controlled studies isolating and measuring the impact of individual design elements would strengthen the evidence base. Despite these limitations, the assessment provides a valuable foundation for iterating on the RoboMaster S1 experience and informing the development of future educational robotics solutions. Continuous user research, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a willingness to adapt based on data and feedback will be crucial for maximizing the product’s potential to inspire and enrich STEM learning.

The design of RMS1 and its application focus heavily on motivational aspects, using elements from Self-Determination Theory (SDT). SDT suggests that intrinsic motivation is enhanced when activities meet basic psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness:

- Competence: Users feel capable as they navigate through different modes, facing challenges that match their skill levels.

- Autonomy: The app offers various choices that empower users to control their learning pathways and strategies.

- Relatedness: Users are part of a community of robotics enthusiasts, enhancing the social aspect of learning.

References#

- Barker, B., & Ansorge, J. (2007). Robotics as means to increase achievement scores in an informal learning environment. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 39(3), 229-243.

- Brophy, J. (1999). Toward a model of the value aspects of motivation in education: Developing appreciation for.. Educational Psychologist, 34(2), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3402_1

- Caron, D. (2010). Competitive robotics brings out the best in students. Tech Directions, 69(6), 21–23.

- Chin, K.-Y., Hong, Z.-W., & Chen, Y.-L. (2014). Impact of using an educational robot-based learning system on students’ motivation in elementary education. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 7(4), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2014.2346756

- E. Janke, P. Brune and R. Studt, “Exposing students to the unfamiliar - Improving software engineering teaching in non-major computer science programs,” 2013 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 2013, pp. 1294-1298, doi: 10.1109/EduCon.2013.6530273.

- Kanda, T., Hirano, T., Eaton, D., & Ishiguro, H. (2004). Interactive robots as social partners and peer tutors for children: A field trial. Human-Computer Interaction, 19(1), 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327051hci1901&2_4

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. McGill, M. (2012). Learning to Program with Personal Robots. ACM Transactions On Computing Education, 12(1), 1-32. doi: 10.1145/2133797.2133801

- Papert, S. (1993). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas (2nd ed). Basic Books.

- Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (2nd ed). Merrill.

- Przybylski, A., Rigby, C., & Ryan, R. (2010). A Motivational Model of Video Game Engagement. Review Of General Psychology, 14(2), 154-166. doi: 10.1037/a0019440

- RoboMaster S1 - DJI. (2022). Retrieved 12 May 2022, from https://www.dji.com/robomaster-s1

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

- Shaffer, D. W. (2006). How computer games help children learn (1st ed). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vygotskij, L. S., & Cole, M. (1981). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (Nachdr.). Harvard Univ. Press.

- Wolpert, H. A. (2008). The nuts and bolts of achieving end points with real-time continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care, 31(Supplement_2), S146–S149. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-s238